Consolidated and compiled By Happy Tarumadevyanto | Independent Consultant | Environmental Asia| happy.devyanto@environmental.asia

This document is a living document and continues to evolve over time. Updates and improvements may be made periodically to reflect new insights, stakeholder input, and changing contexts. Users are encouraged to consult the latest version to ensure the most accurate and current information is being used.

Image courtesy: Happy Tarumadevyanto 2025

The awareness of the need for balanced environmental management has been growing since the 1980s. At the 78th World Forestry Congress, it was emphasized that managing forests involves not only caring for trees but also supporting the communities that live within them. This highlights that for an area to be managed sustainably, social, economic, and environmental aspects must be equally prioritized and thoughtfully integrated into long-term strategies.

In reality, numerous initiatives have been undertaken to improve environmental management. Following the World Forestry Congress, various efforts emerged, including participation in natural resource management conventions, the formation of environmental monitoring institutions, community-based forest management programs (such as Bina Desa Hutan), and many other related activities.

By around 1982, Indonesia introduced the Environmental Impact Assessment (AMDAL) initiative. AMDAL was designed to address concerns raised by environmental advocates about responsible resource management. It is not surprising that many individuals familiar with AMDAL at the time remain involved with its processes today, often recommending its application as a prerequisite before initiating any development projects in a given area.

As a holder of Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) certification schemes that encompass both upstream and downstream operations, LEI seeks to understand the extent to which certification can enhance forest governance.

Similar to other SFM certification systems such as PEFC and FSC, LEI’s approach is rooted in a framework of criteria and indicators it has developed. These are designed, as much as possible, to reflect the practical, day-to-day activities of specific forest management units.

In promoting sound forest governance, LEI formulates its criteria and indicators based on input from a broad range of stakeholders and incorporates insights from academic and field-based research. When applied, these principles and indicators aim to improve forest management practices in a way that supports sustainable livelihoods and enhances the quality of life for communities living in and around forest areas.

LEI serves as a concrete expression of the ecolabel concept—translating it into real, actionable outcomes. The initiative represents a long-standing effort to interpret the principles of ecolabelling in ways that contribute to a more sustainable Indonesia, fostering environmentally conscious practices and responsible resource management.

The Indonesian Ecolabel Institute (LEI) initially aimed to function as an accreditation body, serving as a scheme owner, much like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). The joint certification protocol, which was implemented for approximately ten years, was intended to allow LEI to learn from FSC and vice versa, enabling both to make meaningful contributions to the advancement of sustainable forest management.

Why Voluntary Certification?

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is a globally recognized, voluntary certification scheme that promotes responsible forest management. In Indonesia, FSC has emerged as a valuable alternative mechanism to support sustainable forestry while opening access to eco-sensitive markets, particularly in Europe, North America, and parts of Asia. FSC certification is particularly relevant for Indonesian forest-based industries seeking international recognition for their commitment to environmental and social standards.

Established in 1993, the FSC system was developed in response to growing public concern over deforestation and unsustainable forest practices. It provides a credible, independent framework for verifying that forests are managed in a way that preserves biodiversity, supports local communities, and maintains economic viability. The FSC Principles and Criteria serve as the core standards to assess forest management performance. These standards are globally applicable but adaptable through National Forest Stewardship Standards (NFSS) to reflect specific country contexts, including Indonesia.

In the Indonesian context, FSC certification plays a strategic role. The country is home to extensive tropical rainforests that are both ecologically significant and economically important. However, pressures from illegal logging, land-use change, and weak enforcement of regulations have threatened the sustainability of these forests. FSC certification offers a way for forest managers and companies to demonstrate their compliance with international best practices, thereby enhancing their legitimacy in global markets.

One of the key strengths of FSC certification in Indonesia lies in its market access potential. Many buyers, especially in Europe and North America, prefer or require certified wood products to meet sustainability commitments or due to regulatory obligations like the European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR). As a result, FSC-certified timber products from Indonesia often enjoy greater competitiveness and market differentiation. FSC labeling assures consumers and corporate buyers that the products come from responsibly managed forests, thereby increasing brand value and trust.

Beyond market access, FSC certification has encouraged systemic improvements in forest governance and social responsibility. Certified operations are required to engage with local communities, recognize indigenous rights, and protect high conservation value areas. These requirements help shift forest management practices toward greater transparency, inclusivity, and environmental stewardship. For instance, companies must conduct stakeholder consultations, protect endangered species, and ensure fair labor practices.

The implementation of FSC in Indonesia has not been without challenges. Aligning the FSC standards with national regulations, securing consistent government support, and addressing cost barriers for smallholders remain ongoing issues. However, partnerships between NGOs, certification bodies, community forest managers, and private companies have helped strengthen FSC’s presence and influence in the country.

In conclusion, FSC serves not only as a certification tool but also as a catalyst for transformation in Indonesia’s forestry sector. It promotes responsible forest management practices while providing economic incentives through better market access. For companies, communities, and the environment, FSC represents an opportunity to balance sustainability with profitability, contributing to the long-term resilience of Indonesia’s forest landscapes.

Toward International Generic Standards

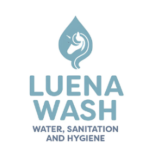

🔹 1993 – FSC Established (Global)

FSC was officially founded as a global initiative to promote responsible forest management through third-party certification based on 10 principles and criteria.

🔹 Late 1990s – Initial Recognition in Indonesia

FSC began to be recognized in Indonesia, mainly through environmental NGOs and export-oriented forestry companies seeking to meet international market requirements.

🔹 Early 2000s – Rise of Demand for Certification

Buyers in Europe and the U.S. started requiring FSC certification. Indonesian exporters and forest managers took interest in FSC to meet these demands.

🔹 2002 – Start of Joint Certification Protocol (LEI–FSC)

A formal cooperation was initiated between FSC and LEI (Lembaga Ekolabel Indonesia). This protocol allowed for dual certification and knowledge sharing between both systems.

🔹 2003–2010 – Implementation of Joint Certification

Several forest management units in Indonesia were certified under this joint protocol. Both LEI and FSC learned from each other’s strengths—FSC’s international recognition and LEI’s local relevance.

🔹 2011 – End of Joint Certification Protocol

The formal joint certification cooperation concluded. FSC continued independently, with several Indonesian certificate holders transitioning fully into the FSC certification system.

🔹 2015 – Development of FSC International Generic Indicators (IGI)

FSC introduced IGIs to harmonize national standards globally. This laid the groundwork for Indonesia to localize the standard through a National Forest Stewardship Standard (NFSS).

🔹 2016–2020 – Development of Indonesia’s NFSS

A multi-stakeholder process involving local communities, companies, and NGOs began to adapt FSC’s IGI to the Indonesian context.

Stakeholder consultation during the development of the National Forest Stewardship Standards (NFSS) in Indonesia was a valuable and transformative experience for those involved in forest certification. It not only shaped the technical content of the standards but also became a platform for building trust, fostering dialogue, and strengthening the integrity of the FSC certification system within the country.

🔹 2021 – Approval of Indonesia’s FSC NFSS

The National Forest Stewardship Standard for Indonesia was approved and began implementation, marking a significant milestone for locally relevant FSC certification.

Accesibility of Standards by Large Scale Companies

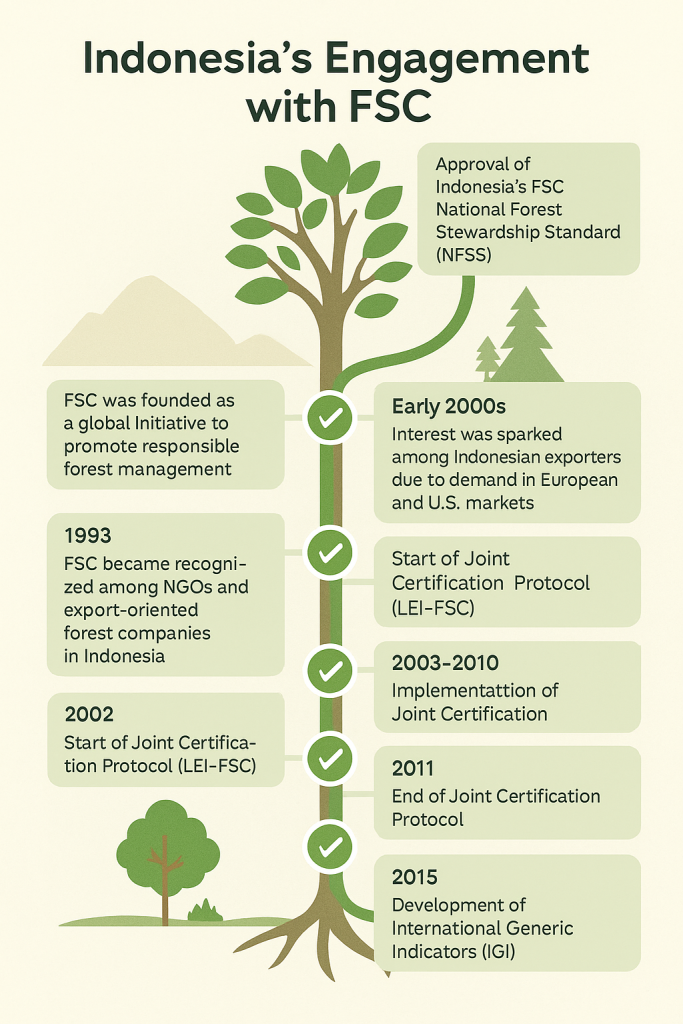

The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) initially faced challenges related to inclusivity during its formation. It was later recognized—around the early 2000s, especially by 2004—that the FSC system, although designed to promote responsible forest management globally, was unintentionally more accessible to large-scale industrial operations than to smallholders and community-based forestry.

This realization emerged from both internal reviews and external feedback highlighting that:

Certification costs and administrative requirements were too burdensome for small-scale operations.

The original standards and processes were not well adapted to the realities of community forestry or indigenous land rights.

As a response, FSC began developing more inclusive mechanisms such as

1. SLIMF (Small and Low-Intensity Managed Forests) standards,nSupport programs for smallholders and indigenous peoples,

2. Efforts to simplify auditing processes and reduce costs for non-industrial stakeholders.

This shift marked an important evolution in FSC’s approach—aiming for a more equitable and diverse certification system that recognizes and supports the unique roles of smallholders in sustainable forestry.

Learning Sustainable Forests Management from Perum Perhutani

The history of Perum Perhutani’s entry into the FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) scheme began in the late 1990s through a pilot initiative led by SmartWood, one of the earliest accredited certification bodies under the FSC system (now part of the Rainforest Alliance).

Here’s a summary of the key moments:

1. Early Engagement (Late 1990s)

Perhutani, as the state-owned forestry company managing Java’s production forests, began exploring FSC certification as part of a global movement toward sustainable forest management. This interest aligned with increasing international demand for certified timber and environmentally responsible practices.

2. Collaboration with SmartWood

Perhutani partnered with SmartWood to assess and improve its forest management practices. SmartWood provided the technical assistance and conducted pre-assessments to determine the readiness of Perhutani’s forest management units (KPHs) for FSC certification.

3. Pilot Certification: KPH Kendal and KPH Cepu

Around 2000–2001, two forest management units—KPH Kendal and KPH Cepu in Central Java—underwent full FSC assessments. These assessments looked at ecological sustainability, community involvement, and legal compliance.

- In 2001, KPH Kendal became the first state production forest in Indonesia to receive FSC certification. This marked a historical achievement for Perhutani and positioned the company as a pioneer in integrating international sustainability standards into state forest management.

4. Impact and Learning

The FSC certification process prompted institutional learning within Perhutani, including:

- Enhanced social engagement with local communities.

- Stronger attention to biodiversity and environmental conservation.

- Introduction of better documentation and monitoring systems aligned with FSC’s 10 principles and criteria.

5. Challenges and Revisions

Over time, Perhutani faced challenges in maintaining certification in some areas due to social conflicts, illegal logging pressures, and institutional capacity. These challenges became valuable lessons in adapting large-scale, state-run forest governance to meet voluntary international standards like FSC.

In essence, Perhutani’s FSC journey through SmartWood served as a foundational experience in transforming state forest management toward global sustainability benchmarks, while also highlighting the complexities of applying FSC in public-sector forestry in Indonesia.

The learning process related to Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) standards within Perum Perhutani began to gain serious attention in the late 1990s to early 2000s. This period coincided with the growing global awareness of sustainable forest management and the increasing demand from international markets for certified wood products.

Specifically:

- Between 1998 and 2001, Perhutani initiated pilot projects for forest certification under the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) scheme in several forest management units (Kesatuan Pemangkuan Hutan, or KPH), such as KPH Kendal and KPH Cepu in Central Java.

- In 2001, Perhutani received its first FSC certification for KPH Kendal, marking the beginning of the application of FSC principles and criteria in state production forests.

- This process served as a valuable learning experience for both Perhutani and the Indonesian government in implementing international standards within the framework of state-managed forests, which have a long history and strong institutional structure.

Therefore, the formal learning of SFM standards through Perhutani began in the late 1990s and has continued to develop through certification implementation, revision of management systems, and integration of social and environmental aspects in forestry planning.

International Generic Standards (IGIs)

IGIs are required to ensure global consistency, credibility, and effectiveness in sustainable forest management under certification schemes like the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).

🔹 1. Standardization Across Countries

IGIs provide a common framework for applying FSC’s Principles and Criteria globally. Without them, each country might interpret sustainability differently, leading to inconsistencies in how forests are managed and assessed.

🔹 2. Ensure Credibility and Comparability

By setting unified indicators, FSC can ensure that certified forests—whether in Indonesia, Canada, or Congo—meet the same core sustainability expectations. This enhances consumer confidence and market acceptance worldwide.

🔹 3. Guide National Adaptation (NFSS)

IGIs serve as the baseline for developing National Forest Stewardship Standards (NFSS). Countries adapt IGIs to their ecological, legal, and social contexts while still aligning with FSC’s global goals.

🔹 4. Support Auditor Consistency

Auditors use IGIs as technical guidance to ensure evaluations are conducted uniformly across different regions and forest types. This improves audit quality and trust in certification outcomes.

🔹 5. Reflect Evolving Global Expectations

IGIs help FSC continuously align with emerging international norms, such as indigenous rights, climate responsibility, and biodiversity protection.

| Year | Remarks | |

| Early Engagement (Late 1990s) | Perhutani began exploring FSC certification as part of a global movement toward sustainable forest management. | Perhutani, as the state-owned forestry company managing Java’s production forests, began exploring FSC certification as part of a global movement toward sustainable forest management. This interest aligned with increasing international demand for certified timber and environmentally responsible practices. |

| Between 1998 and 2001, | Pilot projects for forest certification under the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) scheme in several forest management units | Perhutani initiated pilot projects for forest certification under the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) scheme in several forest management units (Kesatuan Pemangkuan Hutan, or KPH), such as KPH Kendal and KPH Cepu in Central Java. |

| Around 2000–2001, | full FSC assessments. two forest management units—KPH Kendal and KPH Cepu in Central Java | two forest management units—KPH Kendal and KPH Cepu in Central Java—underwent full FSC assessments. These assessments looked at ecological sustainability, community involvement, and legal compliance. |

| In 2001 | Perhutani received its first FSC certification | Perhutani received its first FSC certification for KPH Kendal, marking the beginning of the application of FSC principles and criteria in state production forests. |

| 2000s | Around the early 2000s, | The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) initially faced challenges related to inclusivity during its formation. It was later recognized—around the early 2000s, especially by 2004—that the FSC system, although designed to promote responsible forest management globally, was unintentionally more accessible to large-scale industrial operations than to smallholders and community-based forestry. |

| 2011–2013 | Decline of JCP Activity | Internal shifts in both LEI and FSC led to a slowdown in joint certification. LEI focused more on national-level developments, while FSC strengthened its own global presence with the IGI and NFSS processes. |

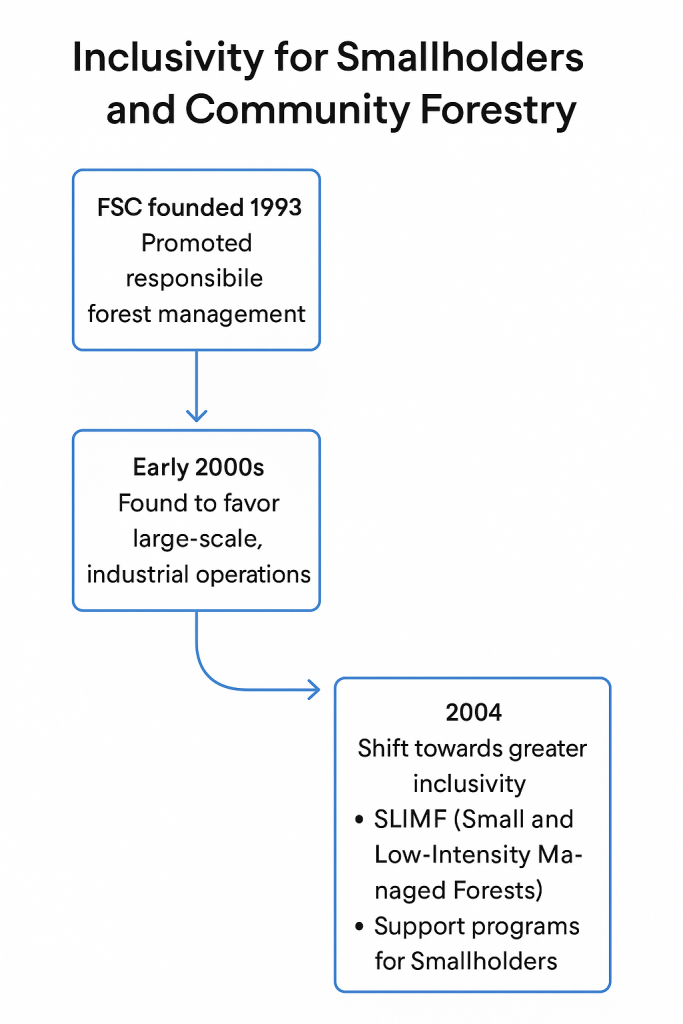

| In summary, 2005–2015 | transition and groundwork | was a decade of transition and groundwork, culminating in the IGI as a major step toward more standardized, transparent, and credible forest certification under FSC. |

| By 2013–2015, | FSC developed and tested the International Generic Indicators, | based on the revised P&C V5, to guide national standard-setting groups in aligning with FSC’s global goals. |

| 2015 | In 2015, FSC released the IGI as a derivative guide from the P&C. | The IGI aims to: Standardize the interpretation of P&C across countries. Serve as a reference for developing National Forest Stewardship Standards (NFSS). Provide minimum indicators that can be adapted to local contexts. |

| 2016 | The adaptation of the National Forest Stewardship Standard (NFSS) to Indonesia’s national context | It was began around 2016, following the release of the International Generic Indicators (IGI) by FSC International in 2015. |

| 2016–2018 | Drafting and initial public consultation of the NFSS | based on the IGI and Indonesia’s legal, social, and ecological context. |

| FSC’s core principle emphasizes multi-stakeholder participation | FSC’s core principle emphasizes multi-stakeholder participation, meaning that every voice—whether from industry, civil society, Indigenous Peoples, academics, or government bodies—has a role in shaping what sustainable forest management looks like at the national level. During the NFSS development, Indonesia applied this participatory principle extensively, making the process more transparent and inclusive. | |

| 2019 | Finalization | Finalization of the draft and submission to FSC International for approval. |

| May 1, 2020: | The final version of Indonesia’s NFSS | The final version of Indonesia’s NFSS was officially approved and implemented by FSC International. |

| June 2023 and will begin full enforcement by December 30, 2024. | a new global regulatory landscape—particularly with the implementation of the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), | The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), as a voluntary certification system for responsible forest management, is currently facing a new global regulatory landscape—particularly with the implementation of the European Union Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), which was officially adopted in June 2023 and will begin full enforcement by December 30, 2024. |

The momentum of FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) Standard Development in Indonesia reflects a growing national commitment to sustainable forest management that balances environmental, social, and economic priorities. Several key aspects underline this momentum:

- Localization of Global Principles: The FSC National Forest Stewardship Standard (NFSS) for Indonesia translates global FSC principles into locally relevant criteria. This adaptation reflects Indonesia’s unique forest governance, socio-cultural context, and ecological conditions.

- Multi-Stakeholder Engagement: The development of the FSC NFSS in Indonesia has involved broad participation, including representatives from government, industry, NGOs, indigenous peoples, and academics. This inclusive approach ensures the standard is both credible and practical.

- Strengthening of Legal and Customary Rights: The FSC standard emphasizes respect for the rights of indigenous and local communities. In Indonesia, where land tenure and customary forest use are often contested, FSC provides a platform for recognizing and protecting these rights within forest concessions.

- Support for Responsible Market Access: As global markets increasingly demand verified sustainable products, the FSC standard offers Indonesian forest managers a competitive edge, especially in export-oriented markets such as Europe and North America.

- Alignment with National Priorities: The FSC NFSS supports Indonesia’s broader environmental goals, such as reducing deforestation, enhancing biodiversity conservation, and contributing to climate change mitigation through responsible forest stewardship.

This momentum positions FSC as a powerful tool for improving forest governance and promoting sustainability in Indonesia’s forestry sector.

1. Development of FSC Principles & Criteria (P&C)

FSC established 10 Principles and over 70 Criteria as a global framework for responsible forest management. These principles are internationally applicable and cover social, environmental, and economic aspects.

History of the Joint Certification Protocol between LEI and FSC

The Joint Certification Protocol (JCP) between the Indonesian Ecolabelling Institute (LEI) and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) was a collaborative initiative that emerged in response to the need for strengthening sustainable forest certification systems in Indonesia. This initiative officially began in the early 2000s and remained active for about a decade.

The collaboration aimed to bridge the differences between LEI’s locally grounded approach and FSC’s global standards. Through the JCP, both parties hoped to achieve mutual recognition, so that forest management units certified through the joint process would be acknowledged by both certification schemes.

The protocol outlined how joint certification audits would be conducted by assessors from both systems, taking into account each scheme’s principles and criteria. As a result, forest concession holders could obtain dual certification (LEI and FSC) through one integrated assessment process.

The main objective of the JCP was to build national capacity, promote context-specific sustainable forest certification for Indonesia, and maintain access to global markets recognized by FSC.

Over time, however, institutional, political, and market-related challenges led to the gradual inactivity of the JCP. Nonetheless, the experience served as a significant milestone in Indonesia’s sustainable forest management history and provided valuable lessons for developing more inclusive and adaptive certification systems.

A brief timeline of the Joint Certification Protocol (JCP) between LEI (Lembaga Ekolabel Indonesia) and FSC (Forest Stewardship Council)

Late 1990s – Early 2000s: The Idea Emerges

- Awareness grew around the need to strengthen Indonesia’s forest certification systems to meet both local and international sustainability demands.

- Dialogues began between LEI and FSC to explore synergies.

2001–2002: Early Collaboration

- Initial frameworks for collaboration were discussed, with the shared goal of mutual recognition and dual certification.

- FSC began to acknowledge the potential of LEI as a national certification body with local strengths.

2003: Joint Certification Protocol Signed

- The formal JCP agreement was signed to pilot joint certification.

- The protocol allowed forest units to be evaluated simultaneously under both LEI and FSC systems using a single audit team with dual expertise.

2004–2010: Implementation Phase

- Several forest concessions in Indonesia received joint LEI–FSC certification, mostly in natural forest concessions.

- Capacity-building efforts were conducted to harmonize audit procedures and deepen mutual understanding.

- Challenges arose in aligning standard interpretations and audit consistency.

2011–2013: Decline of JCP Activity

- Internal shifts in both LEI and FSC led to a slowdown in joint certification.

- LEI focused more on national-level developments, while FSC strengthened its own global presence with the IGI and NFSS processes.

Post-2014: Transition and Reflection

- The collaboration entered a dormant phase.

- LEI continued to operate but with limited influence in global markets compared to FSC.

- The lessons from JCP influenced the ongoing development of FSC’s localized approaches and national adaptation strategies.