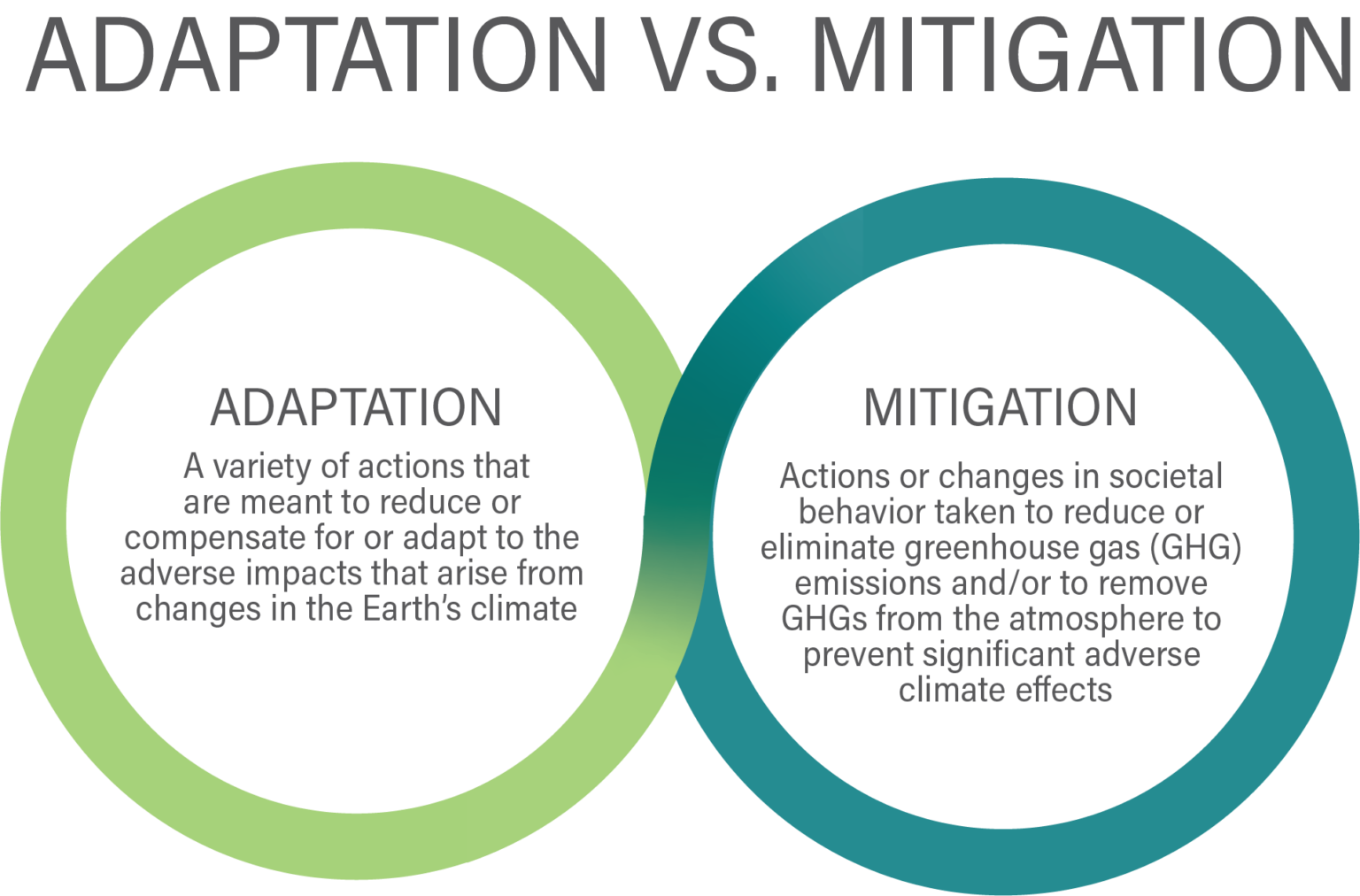

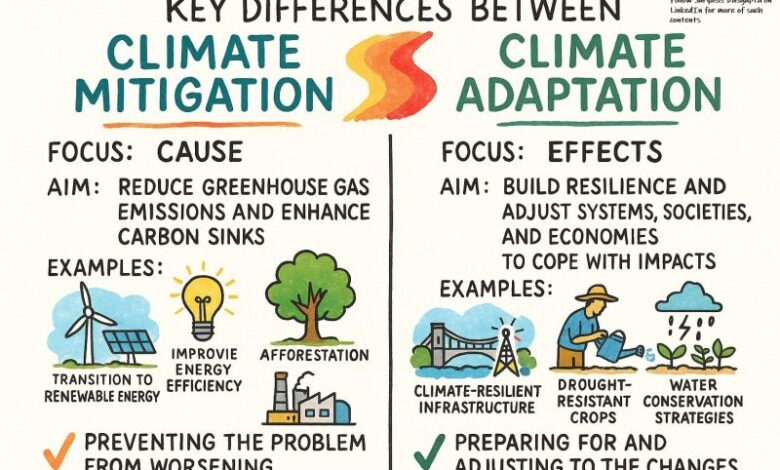

The term “mitigation” has a long history of use in the environmental and natural disasters fields, where it often refers to remedial actions to reduce the impact of an event. It is often confused with “climate adaptation.” Mitigation in climate science is more proactive than reactive.

The first meaning, mitigation, is an effort to reduce the coarseness or fertility (regarding soil and so forth). Meanwhile, the second meaning, mitigation, is the action of reducing the impact of a disaster. Mitigation is a word that has a counterpart in English, which is mitigation. The English definition of mitigation is the action of reducing the severity, seriousness, or painfulness of something. According to the Cambridge Dictionary, mitigation is the act of reducing how harmful, unpleasant, or bad something is.

Efforts in Mitigation aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by shifting to renewable energy, reducing fossil fuel consumption, and preserving forests. Some mitigation efforts that can be undertaken are as follows:

- Switching to Renewable Energy: Utilizing sources like solar, wind, and hydro power to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from power generation.

- Energy Efficiency: Increasing energy efficiency in homes, industries, and using sustainable transportation can also reduce energy consumption and $\text{CO}_2$ emissions.

- Reforestation and Forest Conservation: Protecting forests and carrying out reforestation is crucial because forests are natural carbon sinks.

- Sustainable Agriculture: Sustainable farming practices, such as livestock waste management and reduced use of fertilizers, can also help decrease methane and nitrogen oxide emissions.

- Climate Education and Awareness: Raising public awareness is essential in reducing emissions and adopting a sustainable lifestyle.

Efforts in Adaptation involve steps that can be taken to reduce vulnerability to the existing impacts of climate change. The following steps should be taken as part of climate change adaptation efforts:

- Climate-Based Urban Planning: Cities need to design infrastructure that is resilient to climate change, including flood defenses, urban parks that can absorb water, and buildings designed to cope with higher temperatures.

- Adaptive Agricultural Practices: Farmers need to adapt farming practices by using crop varieties that are more resistant to extreme temperatures and drought.

- Protection Against Natural Disasters: Improvement of early warning systems and emergency planning is needed to protect communities from increasingly frequent natural disasters.

- Development of Weather-Resilient Infrastructure: Infrastructure such as electricity grids, clean water supply, and transportation must be built with extreme weather changes in mind.

The key to tackling climate change is collaborative action from the individual level to the governmental and global levels. Mitigation and adaptation must go hand-in-hand to protect the planet and mitigate the negative impacts of climate change.

Forestry Sector

Engaging in climate change mitigation and adaptation requires significant domestic improvements. While numerous government programs exist, many remain stuck at the planning stage. The implementation aspect urgently needs further improvement.

Crucially, the mindset gap between government policymakers and field implementers—those facing the practical realities on the ground—must be addressed. Effective action demands aligning bureaucratic strategy with on-the-ground operational capabilities and constraints to ensure programs move beyond paper and achieve real impact.

- This viewpoint highlights a crucial challenge: divergent perspectives severely complicate climate change accounting. In Indonesia, the mandated separation of timber products into Natural Forest and Plantation Forest categories is essential but creates complexity. Blending data from these two origins leads to inaccurate volume calculations for wood products. Since these categories have fundamentally different carbon sequestration potentials and harvest cycles, misclassification hinders a precise understanding of the nation’s total timber stock and, consequently, its accurate contribution to climate change mitigation or its carbon footprint.

- It was allegedly A state-owned forest enterprise that released many of its areas to become APL (Area Penggunaan Lain/Other Use Areas), granting cultivation rights to the community, $0.5 – 2$ hectares per household (HH). Some were forced to plant sugarcane, which sells at a low price. Does anyone know if this is part of a scandal involving the transfer of 400,000 hectares of the state-owned land for sugarcane, which is rumored to be owned by a prominent person? However, based on the fact that state-owned forest enterprises do not have the authority to release forest areas (which are their working territory) to become APL.

- The BPS classification of timber species seems misleading. Acacia suddenly appears as its own species group. Yet, according to BPS, which references the Ministry of Forestry (Kemenhut), there are only four timber species groups: Meranti, Mixed Forest (Rimba Campuran), Ebony (Eboni), and Fine Wood (Kayu Indah). Acacia is not included.

Note: I kept the Indonesian terms for the species groups in parentheses as they are specific categories used by Indonesian government agencies (BPS and Kemenhut).

Energy Sector

The introduction of plant-based fuel (BBN or biofuel) products often garners significant attention initially, but their implementation tends to be quieter.

Formally, Indonesia maintains a highly significant mandatory biodiesel program. Currently, the most dominant percentage is B35, which signifies a blend of 35% biodiesel (sourced from palm oil/CPO) with 65% fossil diesel fuel. This program is one of the largest globally and legally mandates the use of BBN in vast quantities. Its goals are to reduce reliance on energy imports and stabilize domestic commodity prices, demonstrating that BBN has entered a phase of serious national-scale implementation.